- Home

- James Skivington

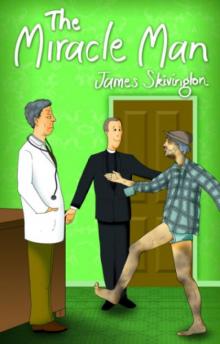

The Miracle Man Page 10

The Miracle Man Read online

Page 10

Dan Ahearn was nudged by Pig Cully who nodded towards a tall young man with wire-framed glasses and a brush of red hair who was leaning against the fence, a notebook and pen in his hands. He was showing a singular lack of interest in the preparations for the forthcoming match which were taking place on the pitch but was looking around the crowd as though expecting to see a friend. Ahearn looked past Cully to the young man and said,

“Looks like he’s taking orders for something. D’ye think maybe he’s from one of them burger vans? What d’ye reckon?”

“For feck’s sake, Ahearn, are ye blind or stupid or both. He’s one of them buckos from the newspapers.”

“Jeez-o,” Ahearn declared, “I think ye’ve got her spot on, Cully! Good man yerself!” And so saying he gave his companion a slap on the back that might have felled a lesser mortal.

“Well now, let’s go and find out what’s in the news,” Pig Cully said and walked towards the young man, cautiously followed by Dan Ahearn who eyed their target warily, as though expecting him to turn on them and bite.

Pig Cully tilted his head back and looked out from under the skip of his cap, giving the object of his gaze a fine view of his nostrils and thus confirming the appropriateness of his nickname.

“You’ll be one of them reporter boys, I suppose.”

Fergus Keane had been with the Northern Reporter for less than a month – his first proper job since scraping a pass in his finals at university the previous year – during which time he had covered funerals, local council meetings, minor sports events and little else. At the advanced age of twenty-three, he was beginning to wonder if he would ever realise his ambition to become an ace reporter whose incisive questioning and investigative skills would lay bare the cankers at the heart of society and rock the very Establishment to its foundations. Perhaps he had already missed his chance. Now he had been sent on some wild goose chase – even his editor, Harry Martyn thought that – following an anonymous telephone call to the newspaper about somebody that claimed to have been the subject of a miracle. It just showed how desperate the paper was for material.

“Yes, sir.” Always better to be extra polite until you knew who they were. He stuck out his hand. “Fergus Keane, from the Northern Reporter.”

Pig Cully was a little taken aback by this familiarity but had automatically responded in kind and so felt obliged to shake the reporter’s hand. Dan Ahearn kept his hands firmly in his pockets. Handshakes were for weddings, wakes and funerals and when you had concluded the sale or purchase of sheep or cattle, not something to be dished out like they meant nothing. The usual toss of the head and, “How y’doin’?” would suffice. So saying, he took half a step backwards. The fella might have extra-long arms.

Further words from the young reporter were drowned out by the shout that went up from the crowd as the Inisbreen team ran onto the field and began to spread out, hurley sticks swinging and chopping the air, chests expanded and contracted, muscles stretched and kneaded. Then the crowd began to get into the spirit of the occasion.

“Did you forget your drawers, short-arse?” John Breen shouted at Tim Sullivan, a diminutive left half-back whose shirt was three sizes too big and came to just above his knees. A series of whoops and shouts came from around the perimeter fencing – “C’mon Inisbreen, show them how it’s done!”, “Run them off the bloody field, boys!”, or “Watch that wee baldy-headed get or he’ll hit ye with his pension book!”

Pig Cully took out his quarter bottle of whiskey and amidst the general excitement forgot the habit of a lifetime and offered the reporter a drink.

“Here, get some of that down ye and ye can shout for the right side. I tell ye, this could be history in the making here.”

“Ah, ye’re right there, Cully,” Dan Ahearn said, slapping his thigh. “History in the bloody making right enough.”

“And I hope ye’re going to report this match fair and square, young fella. We don’t want any – ”

“I’m not here to report the game,” Fergus Walsh said, but his reply was drowned out by the shout that went up as the game started. He shrugged, looked at the whiskey bottle and then took a long swig from it. His subsequent smile of thanks as he handed back the bottle quickly changed to a grimace.

After a few minutes of play an angry shout went up from the spectators as Culteerim were awarded a free. The face of Pig Cully grew redder as he threw a string of abuse at the referee and line judges, each of his remarks echoed by Dan Ahearn at his side. Pig Cully rapped the virgin page of the reporter’s notebook.

“Get that down, boy. Get her down. `Biased referee gave unfair free to a bunch of foulin’ gets from Culteerim.’ Chapter and verse.” Then he looked more closely at the page. “Bejasus ye haven’t even put pen to paper yet. What hell kind of reporter are ye?”

“I tried to tell you, I’m not here for this match. I’ve come to talk to a man called – “ he turned over a page in his notebook, “ – John McGhee? They told me in the village he’d almost certainly be here. Could you point him out to me?”

“Ye want to talk to Limpy McGhee? What the hell for? Even people that know him don’t want to talk to him.”

“Especially people that know him,” Dan Ahearn threw in.

“Well, somebody phoned the paper and said John McGhee was supposed to have had some kind of miraculous cure.”

Dan Ahearn looked at Pig Cully.

“Jeez-o.”

“Oh, it’s the Miracle Man ye want, is it?” Pig Cully scoffed. “Knowing that wee hoor, it was probably him that ‘phoned ye.”

“Well, I – Is he here?” Fergus Keane asked. This was going to be more difficult than he had anticipated, and all for what? Some cock-and-bull story about a miracle, no witnesses, no corroboration. From beneath the skip of his cap, Pig Cully carried out what appeared to be a comprehensive survey of the crowd.

“Oh, he’ll be here somewhere,” was his conclusion, “only I can’t just see him right now.” He turned his attention to the game once more, and after watching it for a minute or so, said,

“If this match doesn’t end in a barney, I’m a feckin’ Dutchman.”

He uncorked his whiskey bottle again and sucked noisily at it. Dan Ahearn also took a bottle out, drank from it and after wiping the top with the sleeve of his jumper, stuck the bottle under the nose of Fergus Keane.

“Here.” The young fella would probably need another drink if he was going to have any dealings with the wee man.

To the young reporter the taste of the whiskey might have been horrid but the warm glow from it was strangely attractive and comforting.

“Thanks,” he said and took a pull from the bottle, remembering to wipe the neck of it with his sleeve before returning the whiskey to Ahearn, who took another drink.

“Yes sir!” Dan Ahearn clapped his hands together and rubbed them in anticipation. “A barney’s what it’ll end up in. Ye have her off to a tee, Cully.”

A bad shot from the Culteerim free-taker brought a cheer from the crowd and then the game settled to a series of poor tackles, missed catches and runs that got nowhere. At half-time the score was two goals and two points to Culteerim and seven points to Inisbreen, who were still grumbling about the unfair free that had resulted in their opponents going one point ahead. As the two teams lay back on the grass or sat drinking from bottles of water, Pig Cully, Dan Ahearn and the man from the Northern Reporter finished the last of the whiskey from both bottles.

“Never fear, my friend,” Pig Cully told Fergus Keane, who was beginning to look a little unsteady on his feet, “Never fear. There’s another one not too far away.”

“Damn right,” Dan Ahearn said, gently swaying back and forth.

From behind them a voice said,

“Well now, boys, how are we doin’this fine day? Enjoying the game’ eh?” It was Limpy that stood there, his chest stuck out like a bantam cock. He was wearing an ancient double-breasted suit that, many years before, he had been asked by a member of the charit

y, the Saint Vincent de Paul Society, to convey to an old man up the glen. On the road, a neighbour had told him that the old man had died in the night and so Limpy had, as he had put it, “diverted” the suit to his own abode, and now wore it on major occasions, regardless of the fact that it had been made to fit a man a stone or more heavier than himself. Now, of course, every day was a major occasion. He had religious standards to maintain.

As Limpy stepped forward, Dan Ahearn swayed back at the overpowering smell of mothballs and stale sweat.

“Well, bejasus, if it isn’t the Miracle Man himself,” Pig Cully said, sweeping his arm in front of him and giving a gracious bow.

“None other,” Limpy said, with a broad smile induced as much by drink as by his burgeoning fame. “None other.”

Throwing his arm round the reporter whom he dragged from his refuge on a fence-post, Pig Cully said, “This here’s the man you were looking for, Limpy McGhee – or maybe we should call him ex-Limpy McGhee – now that he’s a walking miracle man. And this here’s – what’s your name again, son?”

“Fergus Keane, from the Northern Reporter” the young man said mechanically. He seemed to have some difficulty in breathing.

“Well well, the newspapers, eh?” Limpy said, with barely concealed glee. “Word travels fast. So I suppose you’ll be wanting an interview, young Fergus Keane?”

“Eh – if you wouldn’t mind, Mr McGhee,” he replied, although he looked in no fit state to conduct one. He glanced around him, as though seeking somewhere to lie down.

“Ask away, young fella. I’ll tell you all you want to know about the celestial transplant,” Limpy said grandly. He slapped the limb and rose a puff of dust from the leg of his trousers.

“As good as new,” Dan Ahearn averred. “Walks like a regular leg, so it does. You could go far with a leg like that.”

Pig Cully winked at Ahearn and said to the reporter, “No doubt about it, Fergus, you’re witnessing a living miracle in this man here. Brought about by – “ he lowered his head a little, “ – the Blessed Virgin herself.”

“The Blessed Virgin,” Dan Ahearn repeated, as if proposing a toast.

Limpy looked a little put out by these two muscling in on his new-found fame.

“Ye need to hear it straight from the horse’s mouth,” he told Fergus Keane, “and it’s got to be told in the right order.”

“After the exchange of a twenty-pound note,” Pig Cully threw in.

Whether it was because of the bracing sea air or the all-embracing whiskey, Fergus Keane’s lethargic attitude was rapidly dissipating in the face of his mounting interest in Limpy’s case.

“Are you saying, Mr McGhee, that – a miracle really did happen to you?” He turned to a fresh page in his notebook and held his pencil at the ready.

“I certainly am. Five nights ago at the Mass Rock.” He snapped his fingers. “Just like that. One minute the leg was good for nothing – and the next it was a new instrument entirely.”

“As good a leg as ever a man had under him,” Dan Ahearn said.

“Well, no offence, Mr McGhee, but you must realise that it’s a bit, well, difficult to believe. You know, miracles and all that.”

“No offence taken, Young Fergus, but I’ve been certified by the doctor – and the priest, so I have. There’s no doubt about it. I had a limp since the day I was born. They tell me when I was a nipper I even crawled with a limp and they say it was a pitiful sight. And after the other night it was gone entirely. Didn’t she speak to me and tell me she was going to do it.”

“Who?”

“The Virgin Mary, who else?” It now appeared that Limpy had been on familiar if not intimate terms with the mother of Jesus.

“The Virgin Mary – spoke to you?” The young reporter’s eyes widened in wonderment before commercialism intervened. “Have you – talked to any other newspapers about this?” He scribbled something in his notebook. This was more like it. He might even have – the prospect of it made a little shiver of excitement run through him – a scoop.

“Oh not yet, not yet, but it’s only a matter of time, isn’t it? Newspapers, radio, tv. Interviews, photographs. I soon won’t be able to step outside the house for them journalists and photographers. Bloody paternazis. Ah, I tell ye, that bastard Hitler has a lot to answer for.”

“Paparazzi,” Fergus murmured, and then, “You said it happened at some – Mass Rock. Where is that exactly?”

Limpy considered this for a moment and then said,

“I tell you what I’ll do, Young Fergus. If you and me go to the hotel, where we can have a bit of privacy, I’ll tell you the whole story and then I’ll show ye the place it happened. I can’t say fairer than that.”

“Thank you, Mr McGhee. Thank you very much,” Fergus said. “That would be fine.” This was a front-page story if ever he’d seen one, although he had seen very few in his new role as junior reporter, and he was going to be the one to write it. He could see his name above it now, in letters almost as big as those of the headline.

“And we’ll come along to see fair play,” Pig Cully said quickly, turning and winking at Dan Ahearn, who stuck up a wavering thumb and said,

“Fair play, Cully.”

“Just in case any details slip yer memory – Mr McGhee,” Pig Cully added. He slipped his arm round the reporter’s shoulders. “Have ye a car, son?”

“Yes, I have. It’s parked just over there.”

“Then, lead on, boy, lead on.”

After paying for yet another round of drinks, which his three companions seemed able to quaff almost as quickly as he could draw the money from his wallet, with a spinning head but mounting excitement Fergus Keane went to the little wooden telephone booth in the foyer of the Glens Hotel. Judging by the stories which usually made up the front page of the Northern Reporter – “Facelift for Sewage Farm” and “Mother of Twelve Children Is Only Support Of Her Husband” – the editor, Harry Martyn, would be as excited as Fergus about this one. Fergus Keane, ace reporter, was on his way. The only problem was that, as it was Sunday, he would have to telephone the editor at home. Before lifting the receiver, Fergus stood for some moments, rehearsing in his mind what he was going to say, thinking that he should have jotted something down, some bullet points, as Mr Martyn liked to call them.

“Hello? Mr Martyn? This is Fergus.” He could picture the round face and the bald head with its fringe of dark hair above the ears. A thumb and forefinger he could imagine stroking each side of the man’s chin, as though searching for a beard. There would be a large mug of tea handy.

The loud voice came barking down the line.

“Fergus? Fergus who?”

There was a short silence, during which time the young reporter was overwhelmed by a feeling of panic and Harry Martyn’s memory caught up.

“Oh yes, Keane. Where the hell are you, Keane? And why’re you ‘phoning me at home on a Sunday? Good God, as if I didn’t have enough to put up with from Monday to Saturday without being badgered in my own living room.”

“Eh – I’m sorry to have to phone you, Mr Martyn, but I think this is very important. I’m at Inisbreen. Don’t you remember, there’s this man – ”

“Inisbreen? What are you doing at Inisbreen, for God’s sake? I thought you were supposed to be covering that dancing competition at wherever-the-hell-it-was? Does nobody tell me anything around here?”

“But – “ Fergus could feel his whole journalistic career slipping away, “it was you that sent me here, Mr Martyn.”

“Oh, it was, was it? Well, alright then, but next time – keep me informed. How can I run a newspaper if I don’t know where half my bloody staff are?” There was the sound of slurping. “Anyway, what d’you want?”

“Well, Mr Martyn, I think I’ve got – a scoop.”

The slurping suddenly changed to a choking noise.

“A – what?”

“A – scoop, Mr Martyn.”

“A scoop? You’ve been reading too many comic

s, Keane. A scoop’s what you use to lift dog-shit off the pavement.”

With a pained expression on his young face, Fergus swallowed hard and wished he’d taken his mother’s advice and become a teacher.

“Well, Mr Martyn, there’s this man and he claims he’s seen a vision of the Virgin Mary and that he’s undergone a miracle cure to a life-long illness. He definitely appears genuine to me.”

Fergus waited expectantly for the praise that was undoubtedly on its way. Instead, a long sigh slithered down the line from Ballymane.

“Genuine to you? In your long experience in these matters, is that?” But then Mr Martyn softened a little. He’d been young once, although definitely never as green as this guy. “Look, son, your job is to expose these nutters, not take their side. I mean, I hate to disappoint you and all that, but there’s hardly a day passes in Ireland without some lunatic claiming he’s seen a vision or he’s been cured of Christ-knows what. Let’s get back to the real world, eh?” the editor said, his voice rising. “The harsh realities of life, the cut and thrust of politics, the broken homes, the – the – dog mess on the pavements. That’s what this newspaper’s for.”

“For – dog mess, Mr Martyn? Didn’t you just say that’s what a scoop was for?”

“No, not for clearing up bloody dog mess, for . . . Jasus!” There was a short silence and then a barely audible, “God give me patience,” and then louder, but softly, “For community issues, Mr Keane!”

“But this is a community issue, Mr Martyn. And I’m absolutely certain it’s genuine. In fact, positive. And both the Church and the medical profession have upheld his claim.”

The Miracle Man

The Miracle Man